SEAL ISLAND LIGHTHOUSE

Seal Island Lighthouse 1990

Seal Island Lighthouse 1990

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

Contributor: Chris Mills, Assistant Lightkeeper, Seal Island Lighthouse, 1989/90

Sources: Research and personal knowledge.

Photo - © Chris Mills

Description

The 67 foot timber lighthouse on the island is the original, built 1830-31, the lantern is an aluminium replacement installed in 1978. It contains a modern beacon. The Seal Island Lighthouse Museum In Barrington Nova Scotia is a 35 foot high replica of the top half of the Seal Island Lighthouse. It is crowned by the cast-iron lantern which was removed from the light in 1978 and houses the Fresnel Lens which was also removed at that time.

This is the station before it was de-staffed, showing the big double keepers` house.

This is the station before it was de-staffed, showing the big double keepers` house.

Seal Island Lighthouse 1990

Photo - © Chirs Mills

Early History

Seal Island Lighthouse c. 1930

Seal Island Lighthouse c. 1930

Note Second Order lantern and lens, now at the Seal Island Light Museum, Barrington. The building behind the trees on the left houses the steam fog whistle.

Photo - © Courtesy Mary Nickerson

Before anyone lived on Seal Island, shipwrecked mariners lucky enough to have reached its shores alive often died of starvation and exposure during the harsh winter months. By the early years of the nineteenth century a grim spring tradition had evolved, as preachers and residents from Yarmouth and Barrington came to the island to find and bury the dead. There was much concern about the loss of life (on one occasion 21 people were buried in shallow graves in a single day) and in 1823, two families, the Hichens and the Crowells settled on the island in the hopes of assisting the unfortunate souls cast ashore during the winter storms. Richard Hichens himself had been shipwrecked on Cape Sable in 1817 and later married Mary Crowell, who had heard firsthand many stories of the deaths on Seal Island from her father, a Barrington preacher.

After settling on the island, Richard Hichens and Edmund Crowell soon began to petition the provincial government for money to construct a wharf and "for funds for two good boats so that they might better serve shipwrecked sea men." In 1827 a wharf was completed, making it easier for lifeboats to attend to rescues in the area. Later the same year, at the urging of Hichens and Crowell, Nova Scotia governor Sir James Kempt surveyed a location for the erection of a lighthouse 500 metres from the shore near the southern tip of the island. Construction began in 1830; the large wood structure was built of massive squared timbers, 47 feet long, framed and set in a rock and mortar foundation. The lantern floor was reinforced with heavy wood knees, and stout cross members braced the rest of the tower. On the night of November 28, 1831 the fixed light was lit for the first time. A daughter was born to Richard and Mary that same evening, and so began a family lightkeeping tradition that would last more than a century on Seal Island.

After settling on the island, Richard Hichens and Edmund Crowell soon began to petition the provincial government for money to construct a wharf and "for funds for two good boats so that they might better serve shipwrecked sea men." In 1827 a wharf was completed, making it easier for lifeboats to attend to rescues in the area. Later the same year, at the urging of Hichens and Crowell, Nova Scotia governor Sir James Kempt surveyed a location for the erection of a lighthouse 500 metres from the shore near the southern tip of the island. Construction began in 1830; the large wood structure was built of massive squared timbers, 47 feet long, framed and set in a rock and mortar foundation. The lantern floor was reinforced with heavy wood knees, and stout cross members braced the rest of the tower. On the night of November 28, 1831 the fixed light was lit for the first time. A daughter was born to Richard and Mary that same evening, and so began a family lightkeeping tradition that would last more than a century on Seal Island.

The Second Order Fresnel Lens from Seal Island Lighthouse

This lens is now installed at the Seal Island Light Museum, Barrington.

Photo - Kathy Brown

Later History

Seal Island Lighthouse 1997

Seal Island Lighthouse 1997

© Kathy Brown

By the early 1970s, radar and LORAN systems were becoming common in the smaller boats, and the Canadian Coast Guard began to implement their lightstation automation program. At Seal Island the light and horn were semi-automated, and the duties of the keepers reduced to general maintenance. It was a drastic change from the early days when manually operated equipment and watch duties kept the keepers busy 24 hours a day.

The early keepers had been a dedicated lot, as much through necessity as choice. It was a full time job to maintain the light, fog whistle and buildings, as well as raise animals and crops for survival. In 1901, Barrington Notes in a local paper remarked that "John Crowell [Winifred Hamilton's father], lightkeeper from Seal Island, is taking a much needed vacation, his place being filled by Squire Covert of North East Point." It was to be a long time before Crowell took another holiday. His daughter claimed that between 1902 and 1917 John Crowell did not take one day of holidays, nor did he miss one watch at the lightstation. Crowell served as keeper of the light for a total of 36 years. With his retirement in 1927, the light passed out of Crowell hands, although Winifred's husband was appointed keeper and served until 1939 when ill health forced him to leave the island.

By 1986 the keepers' families had been moved off the island and the station changed to rotational status, with two teams of two keepers working alternate 28 day shifts. In 1989 work crews from the Coast Guard Base in Saint John began constructing a new engine room by the tower and installing remote monitoring equipment; by the summer of 1990 the work was complete. At 7:30 in the morning of the 17th of October, lightkeeper James Nickerson transmitted the station's last weather report to Yarmouth Coast Guard Radio. That afternoon, the light became officially unwatched, bringing an end to 159 years of staffed history. Principal keeper Brian Stoddard had departed the island one day earlier, leaving the husband of Mary Hichens great- grandniece to finish duties at the lighthouse for the last time.

The Light Today

Today Seal Island is in a state of decline. Only a handful of houses and sheds, a church and the automated lighthouse remain on an island that once boasted a permanent population, lobster cannery, post office and even a phone line to the mainland. This decline is nothing new for remote lighthouse and fishing islands off the Atlantic coast- many settlements were abandoned in the early twentieth century when gas boats and mainland amenities drew people away from their island homes. 50 years ago Thomas Raddall wrote about Seal Island in a Saturday Evening Post article: "For six months in the year the weathered grey dwellings beside the two coves are ghost villages without a living soul, and even in the lobster season many of them are tenantless and tottering to ruin." Today, the village on the west side of the island has experienced growth in the form of new sheds and fishermen's houses. Clark's Harbour men still lobster from the island, bunking in the old cookhouse above the government wharf.

Today Seal Island is in a state of decline. Only a handful of houses and sheds, a church and the automated lighthouse remain on an island that once boasted a permanent population, lobster cannery, post office and even a phone line to the mainland. This decline is nothing new for remote lighthouse and fishing islands off the Atlantic coast- many settlements were abandoned in the early twentieth century when gas boats and mainland amenities drew people away from their island homes. 50 years ago Thomas Raddall wrote about Seal Island in a Saturday Evening Post article: "For six months in the year the weathered grey dwellings beside the two coves are ghost villages without a living soul, and even in the lobster season many of them are tenantless and tottering to ruin." Today, the village on the west side of the island has experienced growth in the form of new sheds and fishermen's houses. Clark's Harbour men still lobster from the island, bunking in the old cookhouse above the government wharf.

The east side village is a ghost town. A few years ago the breakwall protecting the government landing was washed away and last winter storms tore up the slip way. The freighter Fermont, run aground one year after the last keeper had left the lighthouse, sits hard on the sand of the east beach. Last winter's storms broke its back and tore the rusted hull into two mammoth, ragged pieces. Below Winifred Hamilton's homestead, the last lifeboat sits abandoned, a reminder of the days when the island and its keepers were so crucial to the safety of shipping.

© Courtesy Mary Nickerson

The Hamilton House Seal Island Lighthouse

For seven or eight months of the year, Mary and Jim Nickerson live in a house stone's throw from Mary's mother's homestead. The 1906 church has been refurbished and stands in stark contrast to the decrepit landing and abandoned lobster traps. Nearby, the road to the lighthouse still winds through the scraggly spruce but at the end of the lane the station is deserted. The lighthouse (the oldest operating wooden light in Canada) continues to operate automatically with a small diesel generator powering the light and the fog horn. There is a large aluminum security door on the tower, complete with heavy duty padlock, and a sign warning "No trespassing. Building fitted with intrusion alarm". But there is still a palpable sense of history in the old tower. An incandescent lightbulb on each landing casts a dim light on the huge whitewashed timbers. Names of lightkeepers and visitors, some dating back a century, are scrawled here and there on the beams. Those beams and the braces, the very skeleton of the lighthouse, are the last intact pieces of the past here, and they evoke some of the history of the place.

Wreck of the Fermont on Seal Island, 1997

Wreck of the Fermont on Seal Island, 1997

This ship was driven ashore on the beach on the inner side of the island.

© Peter MacCulloch

Of the older station buildings, only the barn built by Ellsworth Hamilton (Winifred's Husband) and the house used by the radio operator, remain. The duplex, built in 1953 to replace the original Hichens/Crowell house, has been torn down and the domestic engine room has been stripped for it's lumber. Its roof sits partly on the wood floor of the building and grey paint peels off the old engine beds. The huge, red sliding door has been removed from the barn and sheep wander in and out of the gaping entrance. Below the foundation of the old house, the 1870 fog whistle boiler still stands, a rusty, bony finger of iron pointing skyward from the firebox.

The Seal Island lightstation was a constant in the history of the island. It was a government presence, a centre of lifesaving and communications and assistance. Only remnants of the station's past live on, in the stories of Mary Nickerson, and in the broad sweep of the light that continues to guide vessels past the "wicked elbow" of the bay.

As part of the Canadian Coast Guard's review of aids to navigation, some changes have taken place in the past few years at the Seal Island lightstation. The radio beacon, established in 1924, has been discontinued. The lighthouse has been solarized and the diesel generating system removed. The light has been slightly downgraded from 25 to approximately 21 miles range. It is proposed to retain the existing three mile fog horn because of the ledges off the southern end of the island. The station is presently monitored daily (not continuously as in the past) via VHF link by the lightkeepers at the Machias Seal Island Lightstation in New Brunswick

Location

Seal Island lies off the south west tip of Nova Scotia at "the elbow of the Bay of Fundy", where the broad mouth of the bay meets the waters of the open Atlantic. For more than three centuries storms, fog and powerful tides have conspired to wreck scores of ships on the island and it's surrounding ledges. At least 160 vessels have come to grief in the area, making Seal Island historically one of Atlantic Canada's most dangerous areas for shipping, along with Sable and St. Paul's Islands. Although no major wrecks have occurred since the 1940s, the waters around Seal Island continue to command the respect and caution of fishermen and mariners.

Seal Island lies off the south west tip of Nova Scotia at "the elbow of the Bay of Fundy", where the broad mouth of the bay meets the waters of the open Atlantic. For more than three centuries storms, fog and powerful tides have conspired to wreck scores of ships on the island and it's surrounding ledges. At least 160 vessels have come to grief in the area, making Seal Island historically one of Atlantic Canada's most dangerous areas for shipping, along with Sable and St. Paul's Islands. Although no major wrecks have occurred since the 1940s, the waters around Seal Island continue to command the respect and caution of fishermen and mariners.

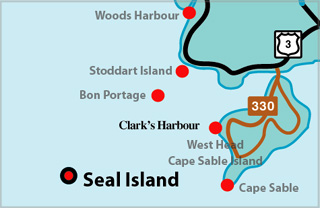

Slightly less than three miles long and between a half and one mile wide, the island is eighteen miles west of Cape Sable Island. A modern Cape Island fishing boat can make the trip from Clark's Harbour in two hours, weather permitting. From a distance, the island is unremarkable, a pencil thin smudge on the horizon. Most of the island consists of glacial till, thickly covered with stunted, wind blown spruce trees. At the north end there are steep gravelly bluffs above the shingle beach. A long sandy beach stretches between granite and gravel bluffs on the east side, and between the north and south ends a long barrier beach and a series of grassy dunes define a brackish pond. Within the forest there are quiet glades where moss covered ground and the winding paths trodden by generations of sheep create an atmosphere of mystery and magic. Hot summer days, placid seas and expansive golden sand beaches belie the vicious storms which led to the destruction of many fine sailing ships in the days before the lighthouse was established.

Visit Seal Island

In the past, NSLPS hosted a guided trip every other summer to Seal Island. Unfortunately, it has been over a decade since NSLPS was able to mount a trip to the island. For information about any upcoming tours, go to the Events and Tours page.

In the past, NSLPS hosted a guided trip every other summer to Seal Island. Unfortunately, it has been over a decade since NSLPS was able to mount a trip to the island. For information about any upcoming tours, go to the Events and Tours page.

In the past, Charles Kenney at Seal Island Tours has taken people out to Seal Island. The island is 2 hours offshore and a trip involves staying at least overnight. His boat is at Clark's Harbour on Cape Sable Island. At this time, we are unaware of the status of Seal Island Tours.

SEAL ISLAND - Light Details

- Location: Southern point of island

- Standing: This light is still standing.

- Operating: This light is operational

- Automated: All operating lights in Nova Scotia are automated.

- Date Automated: Automated by 1990

- Began: 1827

- Date Lit: Nov 28, 1831

- Year Lit: 1831

- Structure Type: Octagonal wood tower, white, red bands

- Light Characteristic: Flashing White (1992)

- Tower Height: 068ft feet high.

- Light Height: 102ft feet above water level.

- Solarized: This light has been solarized.

History Items for This Lighthouse

- 1823 - Hichens and Crowell families began lifesaving station

- 1922 - 1941 - 2nd order dioptric lens - 1930 - compressed air diaphone

- 1959 - converted to electricity - 1870 - fog signal established

- 1978 - original lantern dismantled, reassembled in replica in Barrington

Lightkeepers

Lightkeepers for Seal Island Lighthouse

- Hichens, Capt. Richard 1831-1855

- Crowell, Edmund 1831-1855

- Crowell, Corning 1855-1870

- Crowell Jr., Corning 1870-1891

- Crowell, John 1891-1927

- Hamilton, Ellsworth 1927-1941

- Spinney, Lewis 1941-1946

- Gallant, Edward 1946-1950

- Jeffrey, Elijah 1950-1951

- Flemming, Bradford 1951-1973

- Swim, Maurice 1973-1977

- Nickerson, Jim 1977-1978

- Tiner, Ray 1978-1985

- Penney, Clayton 1985-1990

Highlights

- County: Yarmouth

- Region: South Shore

- Body of Water: Atlantic Ocean

- Scenic Drive: Lighthouse Route

- Site Access: By Boat

- Characteristic: Flashing White (1992)

- Tower Height: 068 ft

- Height Above Water: 102 ft

- Latitude: 43~23~40.0

- Longitude: 66~00~51.0

- Off Shore: Yes

- Still Standing: Yes

- Still Operating: No